| ||

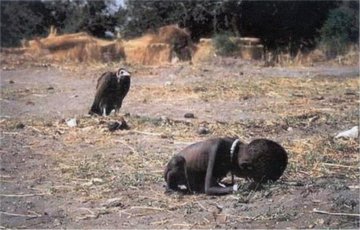

| Via Wikipedia |

“Do not judge, and you will not be judged…” (Luke 6:37)

There’s the everlasting debate about whether photojournalists should intervene in events or merely record them. Are photographers, being objective, dispassionate and distanced while covering violence and tragedy?

Is the moral obligation for a photographer to take an objective photo or to help people in danger?

It is one of the most serious ethical issues in photography.

Let us try to find answers.

Maybe you remember this name – Kevin Carter.

Kevin Carter (13 September 1960 – 27 July 1994) was a South African photojournalist and member of the so called Bang-Bang Club. He was the recipient of a Pulitzer Prize for his photograph depicting the 1994 famine in Sudan. He committed suicide at the age of 33.

Carter grew up in South Africa during apartheid.

He began his work as a sports photographer in 1983, but soon moved to the front lines of South African political strife, recording images of repression, anti-apartheid protest and violence for several South African newspapers and as a freelance photographer.

Carter with three friends - Ken Oosterbroek, Greg Marinovich and Joao Silva - became so well known for capturing the violence that Living, a Johannesburg magazine, dubbed them “the Bang-Bang Club.”

“They put themselves in face of danger, were arrested numerous times, but never quit. They literally were willing to sacrifice themselves for what they believed in,” said American photojournalist James Nachtwey, who frequently worked with Carter and his friends.

In a few short years, Carter saw countless murders from beatings, stabbings, gunshots, and necklacing.

Carter spoke of his thoughts when he took these photographs: “I had to think visually. I am zooming in on a tight shot of the dead guy and a splash of red. Going into his khaki uniform in a pool of blood in the sand. The dead man’s face is slightly gray. You are making a visual here. But inside something is screaming, ‘My God.’ But it is time to work. Deal with the rest later. If you can't do it, get out of the game.”

Carter took a special assignment in Sudan to cover the Sudanese famine. There he took his most famous photograph - the picture of a starving baby being stalked by a vulture.

After Carter took his photographs, he chased the bird away, sat under a tree, lit a cigarette, talked to God and cried. “He was depressed afterward,” Silva recalls. “He kept saying he wanted to hug his daughter.”

I Sit and Look Out

I sit and look out upon all the sorrows of the world, and upon all oppression and shame;

I hear secret convulsive sobs from young men, at anguish with themselves, remorseful after deeds done;

I see, in low life, the mother misused by her children, dying, neglected, gaunt, desperate;

I see the wife misused by her husband - I see the treacherous seducer of young women;

I mark the ranklings of jealousy and unrequited love, attempted to be hid - I see these sights on the earth; I see the workings of battle, pestilence, tyranny - I see martyrs and prisoners;

I observe a famine at sea - I observe the sailors casting lots who shall be kill'd, to preserve the lives of the rest;

I observe the slights and degradations cast by arrogant persons upon laborers, the poor, and upon negroes, and the like;

All these - All the meanness and agony without end, I sitting, look out upon, See, hear, and am silent.

(Walt Whitman (1819 - 1892). Leaves of Grass)

When this photograph was published in the New York Times on March 26, 1993, it opened up the everlasting debate about whether journalists should intervene in events or merely record them.

People wanted to know what happened the child, and if Carter had assisted her. The Times issued a statement saying that the girl was able to make it to the food station, but beyond that no one knows what happened to her.

The photograph does not tell the full story of what happened that day.

As Leslie Maryann Neal wrote: “… he shot the famous vulture photo. He spent a few days touring villages full of starving people. All the while, he was surrounded by armed Sudanese soldiers who were there to keep him from interfering. …even if he decided to help the little girl, the soldiers wouldn’t have allowed it.” (read more here)

The reporters had been told not to touch the Sudanese because many were carrying diseases. There were also conflicting reports about the situation in Sudan. Some claimed that the mother of the child was behind the photographer waiting for food; that once the photo was taken that Carter chased the vulture away and the child wasn't in danger from the bird.

Carter was a photojournalist, a profession with the principle of recording what happens without interfering or having an effect on it. It is not right for those that were not there to judge what Carter should have done.

But the controversy only grew when, a few months later, Kevin Carter won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo.

Some journalists called his prize a “fluke”. Many people said that Kevin Carter was inhumane. He was accused of not helping the child.

“The man adjusting his lens to take just the right frame of her suffering,” said the St. Petersburg (Florida) Times, “might just as well be a predator, another vulture on the scene.”

Why didn’t he help the little girl, they asked. The only way he knew how to help was by taking photographs. Kevin Carter did what a photojournalist is supposed to, and he captured one of the most horrific images ever thinkable.

He created such thought provoking work that became a metaphoric representation of Africa’s despair and helped to draw enormous attention of the world to a terrible famine - and prompt governments to provide aid to the victims. And that might save thousands of lives.

Only 6 days after Carter won the Pulitzer, the Bang-Bang Club made their way to Tokowa to photograph an outbreak of violence there. At around noon, Carter returned to the city, and heard later that Oosterbroek had been killed in the conflict, and that Marinovich had been seriously wounded. It was obvious to his friends that Carter blamed himself for Oosterbroek's death.

“Carter felt it should have been him, but he wasn’t there with the group that day because he was being interviewed about winning the Pulitzer. That same month, Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa.

Carter had focused his life on exposing the evils of apartheid and now—in a way—it was over. He didn’t know what to do with his life.

Soon after, in the fog of his depression, he made a terrible mistake. On assignment for Time magazine, he traveled to Mozambique. On the return flight, he left all his film–about 16 rolls he had shot there–on the plane. It was never recovered. For Carter, this was the last straw. Less than a week later, he was dead. He drove to a park, ran a hose from the exhaust pipe into his car, and died of carbon monoxide poisoning.” (Read more here)

An excerpt from Carter's suicide note: “I'm really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist...depressed ... without phone ... money for rent ... money for child support ... money for debts ... money! ... I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain ... of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners... I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.” (Ken Oosterbroek, one of his closest friends who was killed during a fire-fight that the group was photographing).

Jimmy Carter, Kevin's father, told the South African Press Association that his son always carried around the horror of the work he did. In the end it was too much.

“Few journalists saw as much violence and trauma as he did,” says MacLeod (who was TIME's Johannesburg bureau chief for several years). “Ambition and a search for glamour and excitement were clearly part of Carter’s makeup. But to go into that kind of danger over and over again requires a strong sense of mission or idealism.” (Read more here).

“It is ironic that Kevin Carter won the Pulitzer for a photograph which to me is a photograph of his own soul and epitomizes his life. Kevin is that small child huddled against the world, and the vulture is the angel of death. I wish someone could have chased that evil from his life. I'm sure that little child succumbed to death just as Kevin did. Both must have suffered greatly.” (Joanne Cauciella Bonica Massapequa, New York) (Read more here).

According to Eduard Steichen “The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself”.

In my personal opinion Kevin Carter’s photography fulfilled such a mission.

P.S.

The Truth about malnourished baby and the vulture.

In 2011 The Spanish newspaper ‘El Mundo’ wrote an article about the truth, the real story behind the photograph. They showed that if one observes the high resolution picture, it can be seen that the baby, whose name was Kong Nyong, is wearing a plastic bracelet on his right hand, one issued by the UN food station. On inspecting it, the code ‘T3′ can be read, This means that the baby had survived the famine, the vulture and the tragic public predictions. ‘El Mundo's' reporter, Ayod, traveled to the village in search of the whereabouts of the child. His search led him to the boy's family. The boy's father confirmed his name and said he was a boy and not a girl as previously believed. He told the reporter that Kong Nyong recovered from the famine and grew up to become an adult, however, he said, he had died four years prior to the reporter's visit. (Read more here).

No comments:

Post a Comment